This is the demonstration I keep in my “back pocket” and break out when I cover a class for another teacher. It doesn’t require any equipment and it’s bomb proof: it works every time, and you can use it to start discussions about hypothesis testing, or just get students cognitively engaged in thinking about how their own memory systems work.

The demonstration can also start super useful discussions with students about how they might do more useful cognitive work in class, and with teachers about how they might communicate ideas with students more effectively. It is a replication (sorta) of research done by Alan Baddeley. see the more complete write-up of the demonstration here – Baddeley’s Three Systems of Working Memory . Here’s a brief outline:

- Ask students to close their eyes.

- Instruct them to mentally count (don’t count out loud) the number of windows in the place where they live. They can open their eyes when they are done.

- Ask them to close their eyes again and say “Please count the number of words in the sentence that I just said.” Repeat that sentence a couple times.

- As they try to do that task, you might see them counting on their fingers. That’s a good sign.

- When most of them are done, ask them to open their eyes.

- Ask “How many of you used your fingers when you counted the windows?” One or two people might raise their hands (often no one will).

- Ask “How many of you used your fingers when you counted the words?” Almost everyone will raise their hands.

- Start a discussion about why that happened. These are two very similar mental counting tasks. Why did almost all of us use our fingers on the word task but not the windows task?

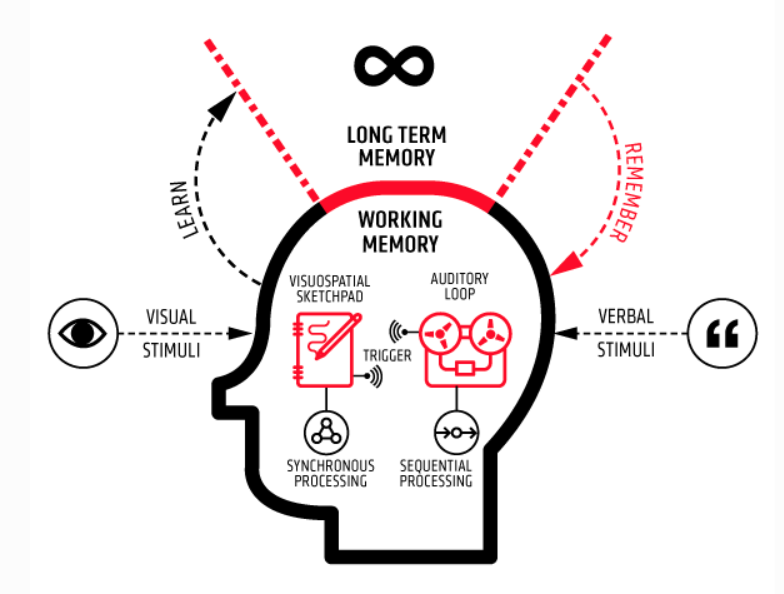

At this point you can list proposed explanations (hypotheses) on the board and alter the task to test them one by one, if you have time. Some explanations may get close to Baddeley’s and other cognitive psychologists’ findings: it turns out that working memory is a complex system with important “moving parts.” I like to think of these aspects of working memory as a boss and two employees (the great graphic by O. Caviglioli at the top of this blog post might help visualize these employees):

- The boss is the “central executive” – this part of working memory monitors incoming information/stimuli and figures out what to do with it.

- The visuospatial sketchpad employee: deals with images

- The phonological loop employee: deals with numbers or words.

The specialties of your two employees explain this strange difference between these mental counting tasks. During the “count the windows” task, the central executive tells the visuospatial sketchpad employee to picture each window, and the phonological loop employee counts each one. Easy! No fingers needed! BUT during the “count the words ” task, the central executive needs someone to repeat the sentence that was just said since the sentence is made up of words. The phonological loop employee is perfect for that task. But now the central executive has a problem: the visuospatial sketchpad employee can’t count! So almost all of us need to use our fingers to count the words in the sentence. (Note: if you’d like to read more about this research, check out Dual Coding theory)

Cool, right? But it’s more than just cool: this detail about how our working memory operates implies some potentially important lessons for students and teachers:

Implications for studying: since we can’t concentrate on words coming in from two different sources at the same time, we may want to be careful about taxing our “cognitive load” for incoming verbal information. This may be why many of us find it difficult to read or process words while there is music with lyrics playing in the background. But the potentially more important implication for studying is that we may want to use graphics or diagrams as we study and try to make sense of words in our notes or a textbook. We can use our visuospatial sketchpad (images/diagrams) and our phonological loop (words and numbers) simultaneously to deeply process meanings and make them easier to recall later. Check out this Learning Scientists blog post for great “dual coding and studying” ideas.

Implications for teaching: After reading dual coding theory, I realized to my horror that one of my teaching habits is a BAD idea: I used to project slides with a bunch of words on them, and I would then talk over the slide, including examples of the concept, elaborating on the ideas, etc. I thought I was helping, but what I was probably doing for most students is overloading their phonological loops. Many students were probably trying to process the words on the slide (in their working memory, using their phonological loop), AND trying to understand what I was saying at the same time, overloading the same working memory system. Oops. Now I try to include only a few words on a slide (or an image) and then I talk through the concept, so that students’ phonological loops and working memories stand a better chance at processing the concept we’re discussing. Related idea: Just add blank slides.