Background: I got to give a TedX Lincoln talk in Oct. 2015. It was a powerful experience, and I’m grateful for the opportunity.

Slides for the talk (slides created by the always awesome Chris Pultz!)

Video of the talk (and yes, my darn tie is crooked the ENTIRE time)

When I took my current job as a Lincoln Public Schools administrator, one of the first projects I wanted to work on was how to give good advice to teachers about classroom assessment. I decided to interview one of my former students, Alex, who was teaching high school students labelled “at risk”. I walked into his classroom after school with my set of carefully designed questions, opened my laptop, and was about to ask the first question, when he politely interrupted me. He said “Mr. Mac, I hope this doesn’t offend you, but I became a teacher because I realized that what I really learned in high school was how to get an A, and not much more than that. I want something better for my high school students.” He was talking about was the game of school. Alex’s comment stopped me in my tracks, and started me down the road of thinking about the differences between playing the game of school and real learning and real teaching. That’s is an important difference. It’s time to rethink the game of school.

You all know the game of school although you may not call it that: we play the game when we focus more on how to get by in a class, how to get an A, what do do for points, rather than focusing on any of the LEARNING in the class. The words we often use reveal some of the elements of this game: “How many points is this worth?” “What’s my score on a test” “What did she/he give you on that paper?” “Can I get any extra credit points?” Class rank, GPA, and a bunch of other school traditions reinforce the message that the goal of school is to accumulate points/grades/credits and win in the end. The game of school isn’t the same as learning, and it might get in the way. Every day in classrooms teachers help students who are convinced that they CAN’T do something, that they aren’t “math people” or “artists” or “writers,” and they get them to use some feedback and SEE that they CAN and DO get better at something important. Teachers help students turn losing streaks into winning streaks. Learning is an experience that changes you, changes the way you think about yourself and the world. This is a tough thing to measure well, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Comparing real learning to the game of school is like comparing love to the number of likes you got on Facebook.

A similar game of school gets played outside the four walls of the classroom too: The No Child Left Behind education reform act encouraged schools and districts to play very strange school games, all based on accumulating points and getting the high score. The premise of this game is that students, schools, and districts should be judged by single scores: averages on statewide achievement tests. If your school or district got below a certain score for a certain year, you were labelled “needs improvement,” No other information gets included in this label – just test scores.

Think about how strange this game is: that something as complex as teaching and learning should be judged by a single “score,” that these goals could be meaningfully represented by one overall grade or rank. Why would we ever think that’s a good idea? Measurement experts and other researchers don’t think it’s a good idea: they stress the importance of using a variety of data to make educational decisions.. Sports fans don’t think it’s a good idea: think about the complex set of statistics and judgments people use when thinking and talking about who the best player or team is from a certain era. I bet YOU don’t think it’s a good idea: if someone asked you to describe your favorite teacher, would you stop, look thoughtful, and simply reply “96.3% – an A.” ? We know that teaching, learning, schools, and districts are complex places doing complex work – why would we think that a single score can describe this complexity?

Playing the No Child Left Behind game of school has consequences. These are headlines from a single day, retrieved from Google News. These headlines are meant to scare us, to convince us that the sky is falling and that our schools in general are failing kids. But it’s all based on a game, and the game is set up to ensure that some schools will always be “needs improvement.” That makes great headlines. This “sky is falling” narrative can be paralyzing – we can become so fearful that we might avoid important decisions, and our vision gets “narrowed” because of the fear of evaluation. Teachers and schools might feel compelled to narrow their vision of education to only what is tested, and test preparation can edge out important learning experiences.

Learning isn’t a simple input/output system easily measured and “incentivized.” It’s not something that just happens as a nice side effect when people seeking points and keeping score. It’s not like a video game. Teachers don’t get to “zap” learning “into” students. Teaching and learning are creative acts, requiring vulnerability, insight, emotions, and struggle. Learning is, literally, creating meaning. We connect what we learn to other experiences and insights, weaving new ideas in with previous notions. Teachers don’t “give” learning to students. Teachers use the medium of curriculum and set up contexts that help students create meaning.

We don’t have to accept this strange game of learning set up by NCLB and policies like it. We can rethink it. We don’t have to pretend that the game of school is the only thing that matters. Instead of just summarizing tests with one overall score or rank for a school or district, why can’t we tell a more rich story? Why not tell several important stories about schools, including test scores but also including maybe graduation rates, college and career placement, student engagement, parent perceptions, effective use of funds, and innovative teaching? And perhaps schools and communities could be part of telling their OWN story, including their own strengths and weaknesses?

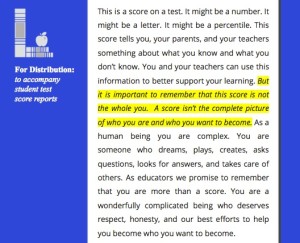

We can push back on the sky is falling mentality of NCLB, and acknowledge that real schools and real students need help solving real problems. We can remember, and remind other people, that tests can tell us import ant information, but they don’t paint the whole picture, and we shouldn’t pretend they do. I’m proud of my co-workers in the Assessment and Evaluation Department – whenever we can in “official testing letters” we tell students and parents that “it is important to remember that this score is not the whole you. A score isn’t the complete picture of who you are and who you want to become.”

ant information, but they don’t paint the whole picture, and we shouldn’t pretend they do. I’m proud of my co-workers in the Assessment and Evaluation Department – whenever we can in “official testing letters” we tell students and parents that “it is important to remember that this score is not the whole you. A score isn’t the complete picture of who you are and who you want to become.”

My favorite quote about teaching and learning is “I have come to believe that a great teacher is a great artist … Teaching might even be the greatest of the arts since the medium is the human mind and spirit.” — John Steinbeck “On Teaching” 1955 If you think about teachers and students as artists, and how limiting and tough it is to measure and evaluate artistry, we can get a sense of how humble and cautious we should be about “grading” “ranking” “judging” teaching and learning.

I want to finish my story about the conversation with Alex. After he said that what he learned in high school was how to get an A, I took a deep breath, and I closed my laptop. I didn’t ask any of my carefully prepared questions. I started listening carefully, and I hope I never stop. It turns out that helping teachers and students means listening rather than starting with the presumption that you have the right advice to tell them.

Learning gets created in classrooms, through educative relationships between teachers and students. I think that simple sentence describes a process that is human, important, beautiful, and one of the most vital parts of our lives. It’s not a game – it’s teaching and learning, and it’s too important to play with.