When I was a new teacher, I used what I now call the “oh crap” model of assessment: I would teach for several days, students and I would have great conversations, and then I would realize after a while “Oh crap! I haven’t put any grades in the gradebook!” I would hurriedly make a quiz or homework assignment, get it out there to students, put those grades in the gradebook, and rush back to teaching and those great conversations.

Eventually I wised up (at least a bit) and started planning farther ahead. I stopped viewing assessment as an annoying responsibility instead of an important part of teaching and learning. I thought about how I wanted to operationally define learning in my classes and designed assessments that gave students a chance to show what they knew and could do. But it took me too long to realize why I needed better classroom assessment habits. It should be so obvious: teachers need evidence about what students are learning.

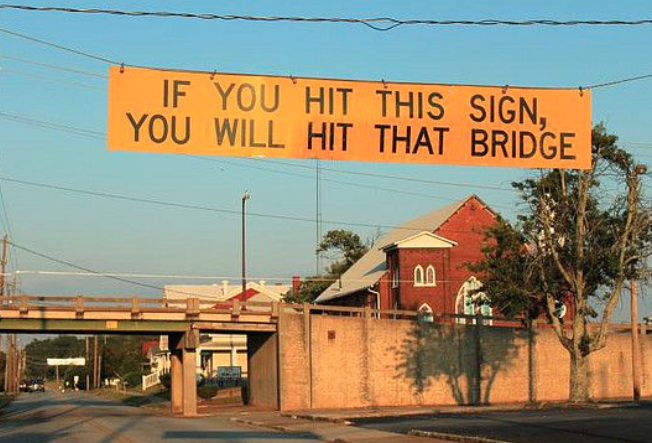

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/bgentry/3853508189/

As teachers we need to know what students are learning so that they don’t “hit that bridge” when test time comes (and, more importantly, when they need to use what they learn from our classes in their lives). Why did I ignore this obvious need as a young teacher?

Because assessment is uncomfortable.

I think people who have never been in charge of a classroom may not be able to relate to this teaching reality: teaching is intimidating and scary, especially as a new teacher. We don’t know if we’re “doing it right.” We may have gone through years of training, but there is no amount of training that can prepare you for the moment when you are flying solo and teaching your own classes. We desperately want to do right by our students. We care. We know there is important knowledge and skills students need to learn. Checking to see what they actually learned is important, but it’s also uncomfortable. We may end up staring at evidence that what we are doing isn’t working. It is much easier to just keep “teaching” instead of stopping to check to see what students are learning. Cognitive psychologists teach us about confirmation bias: we usually look for evidence that confirms our existing beliefs. Confirmation bias can lead us as teachers to keep cruising along, teaching in comfortable ways, instead of seeking out potentially uncomfortable evidence about what our students aren’t learning.

Assessment Discomfort Influences How Students Study

This assessment discomfort can influence how we teach, but it also influences students. Two recent, fantastic books about how students study lay out the empirical evidence for studying methods in elegant, well supported arguments: Regan Gurung in Study Like a Champ and Daniel Willingham in Outsmart your Brain explain the mountains of cognitive psychology evidence behind advice for students about how to study (short version: studying techniques that require more thinking result in more learning. These are both GREAT books every teacher should read!) But they also explain why students tend to avoid these effective studying methods: they are uncomfortable! It’s comforting to read a chapter, think you understood it, then re-read the chapter to make sure we “got it.” This re-reading gives us a warm, comforting feeling of “oh yeah, I remember that!” and we convince ourselves we learned something. In contrast, reading a chapter, closing the textbook, getting out a blank sheet of paper (or new google doc) and writing down everything we remember from the chapter probably feels awful. This much more effective studying method is uncomfortable: we are likely to produce evidence of how little we learned from one reading of a chapter. That stinks. It’s uncomfortable. But we learn MUCH more from this uncomfortable studying technique than the comfortable, feel good re-reading of a chapter.

Assessment Discomfort Influences Teacher Conversations

I love talking with teachers about their teaching. Usually these conversations involve lessons they just designed, compelling stories they love to use with students, and new resources they are excited to share. Rarely do these conversations involve assessment evidence (often only when I bring it up, and this suggestion is sometimes met with uncomfortable silence). Why? Because it’s a conversation killer. If someone is telling you about a new insight they are excited about and you immediately ask “Wait, what’s your evidence that’s true?” it tends to stop the conversation. My friend (and great teacher) Casey Swanson said one of the best pieces of advice he got was when an experienced teacher said “You talk a lot about teaching. How about we talk about learning for a while instead?” Teachers like to talk about teaching. Our first impulse usually isn’t to talk about evidence of student learning, but that (potentially uncomfortable) conversation might be more important than sharing another great lesson plan.

I learned long ago to never include the word “assessment” in any conference proposal I write. Every time I used assessment in the title of a proposal it got rejected. We want our students to overcome the discomfort caused by testing themselves because we know they learn best when they figure out what they don’t know. As teachers, we should overcome our discomfort at testing our teaching. Talking about student learning, and evidence of student learning, may start the most important conversations.