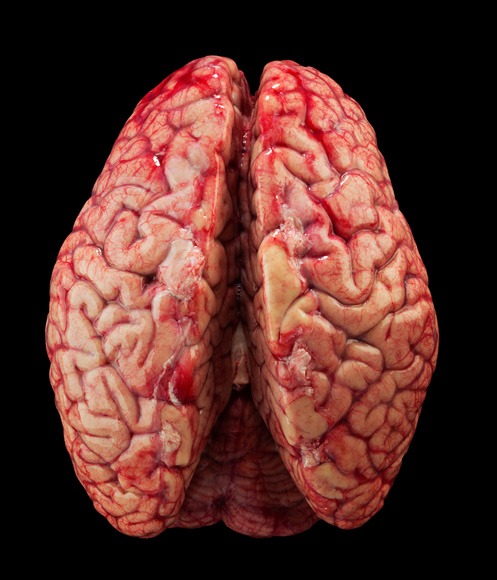

When I taught psychology to high school students, I LOVED teaching them about the brain. I loved sharing the amazing details about this most amazing object in the universe that they carry around with them in their skulls. I loved sharing brain research with them – students often told me that the time we spent talking about Gazzaniga and the split-brain patients were a highlight of the class. I love reading about contemporary brain research (although I often suspect that I don’t have the background knowledge needed to evaluate some of the claims in the sources I’m reading).

Given my love of brain research and my love of teaching, I am also interested in a related topic: What should teachers know about the brain? So far, what I’m learning surprises me a bit.

Daniel Willingham and David Daniel tackle this question head on in one of their “The Daniels” video blogs (which are all a lot of fun, by the way. Daniel Willingham and David Daniel. Get it?) In this short video, they effectively discuss a 2013 Educational Researcher article called “Infusing Neuroscience into Teacher Professional development.” The Daniels conclude that the article doesn’t have much to say about whether brain research is truly “actionable” by teachers. Teachers can definitely learn about brain research, but does it actually help teachers make decisions? They conclude that the answer (so far) is no. For example, knowing that speech is controlled by two specific areas in the left hemisphere of the cerebral cortex is fascinating for all sorts of reasons (check out that Gazziniga split-brain research I mentioned earlier!) , but it doesn’t help me decide how to teach reading, or speech, or anything else.

Andrew Watson tackles a similar question in his great ResearchEd video “Won’t get Fooled Again.” About 17 minutes into the video, he describes a scenario in which a presenter helps teachers understand neural anatomy and the process of neural transmission (another one of my favorite topics in my high school psychology class. We even took a field trip to the bathroom!) After the fictional staff development is over, he wonders what would happen if one of the teachers asked: “Now that I know some information about the brain, how should I use that information to make teaching decisions?” The answer is: you can’t. There are all sorts of great reasons to learn about neural anatomy and function, but this knowledge doesn’t help us make teaching decisions.

And I was excited when I received my “Learning and the Brain” issue of Educational Leadership. I read through the articles eagerly, and gradually got more and more… perplexed. The articles were well written and researched, and I enjoyed learning some recent research about the brain. But I didn’t find discussions of how the brain research directly applied to teaching decisions (or when they did, the application suggestions were based on memory/cognitive/motivation research, not specifically brain research). The last two articles (Education’s Research Problem and Retrieval Practice: A Power Tool for Lasting Learning were very practical and useful, but the advice from those authors was not based on brain research).

So what should teachers know about the brain? Right now, my answer is “As much as they are interested in, but what you learn won’t be your most powerful tool for making teaching decisions.” Learning science/memory/cognition research is much more immediately applicable to decisions about teaching and learning (for example, see Stephen Chew’s excellent “Learning in Pandemic times” video.)

BUT maybe this won’t be true forever! I got to talk (via Twitter) with a neuro/bio researcher who is writing about physiological research that may be developing into more effective/accurate models of memory and learning than some current models (thanks Erica Kleinknecht! ) Specifically, her essay “Labels on the Brain” is great reading. I’m not sure I have the background knowledge yet that I will need to evaluate the effectiveness of competing models, but I’m interested in learning!