I learned about schema theory and memory from S. Chew’s article “Having Knowledge Is Not the Same as Using It” (thanks Steve! Download available here from Researchgate) and I keep thinking about applications for teaching and learning. It’s my new favorite thing!

As Steve describes in the article, schema (mental rules we use to organize the world) influence how we encode (or don’t encode) new information about the world. After I read Steve’s article, I got curious about how I missed learning about schema theory, and I think I figured it out: for some reason, schema theory is not referenced in the context of memory in the AP Psychology curriculum (that’s my primary teaching context), but it is in the IB curriculum. This seems like an oversight! Schema theory is MUCH more useful and important than many of the details AP Psychology teachers have to teach (e.g. the difference between retroactive and proactive interference – ugh!)

In his article, Steve describes research from Bransford and Johnson (1972) that involves reading a paragraph aloud to participants and testing their memory of the information from the paragraph. Their study was designed to measure the impact of listeners having or not having a useful schema for the paragraph before they get to hear it. If you didn’t jump ahead to to the article already, you can try this for yourself: read the paragraph below and think about how confident you might be if someone gave you a pop quiz about this information:

“The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange items into different groups. Of course,

one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere

else due to lack of facilities that is the next step, otherwise, you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run this may not seem important, but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first, the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then, one never can tell. After the procedure is completed one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, this is part of life”. (Bransford & Johnson, 1972, p. 722)

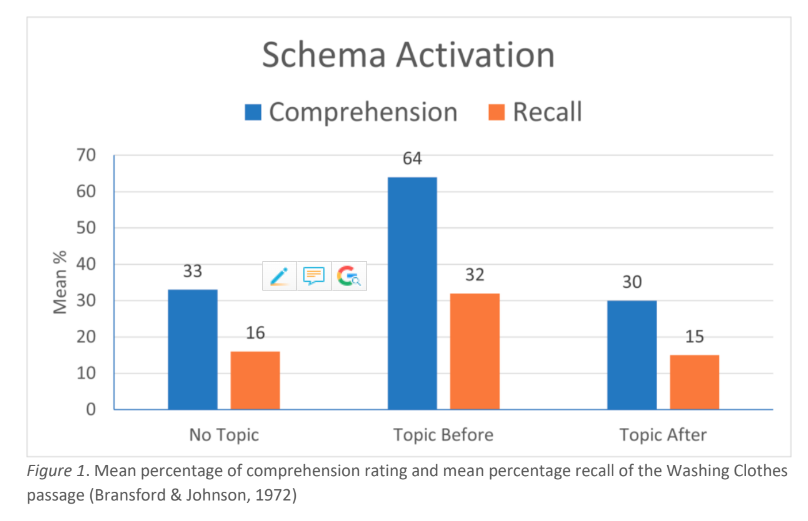

The feeling of confusion or lack of confidence you may be feeling right now may be similar to how many of Bransford and Johnson’s participants felt. Some of the participants heard that paragraph without any previous information. But others got this crucial piece of information – a schema – before hearing the paragraph: “This paragraph is about washing clothes.” Knowing that schema before hearing the paragraph impacted what they learned:

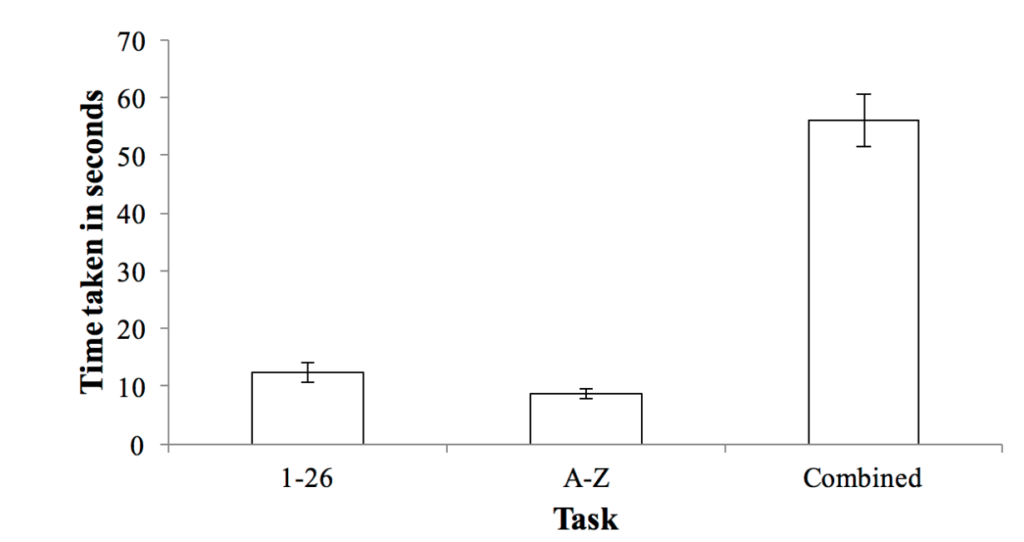

Steve does a great job in the article discussing aspects of this study that are important for teachers: participants who knew the topic of the paragraph before hearing it did better on both the comprehension and the recall measure in the study. But participants who got that information after they heard the paragraph did no better than participants who never learned the topic! There are schema students need BEFORE they go through a learning experience in order for that experience to be useful. If students don’t have the right schema, the learning experience might be a waste of time.

I talked about this experiment with science teachers recently and it started a great conversation. I first handed out a slip of paper to each teacher (pg. 2 of this handout). The teachers didn’t realize that half of them got the version of the instruction with the schema and the other half got the version without (I dealt off the top of the pile to half the room and off the bottom to the other half). Then I read the paragraph (pg. 1 of this handout) and was going to tell them whether they were group A or group B and ask that they fill out this google form (we didn’t go through with the data collection b/c it would have been tricky to ask everyone to use devices at that moment in time).

The science teachers and I had a great discussion about the implications of schema theory for teaching and learning. They immediately understood the importance of this theory for their classrooms, but they pointed out a subtlety I didn’t think about before: they often want to give students the opportunity to experience a phenomenon as a “hook” toward the beginning of a lesson or unit, and then follow up with direct instruction, etc. about the details and terminology about the phenomenon. They noted that students absolutely need the required schema before they experience the phenomena (so that they can think about it in useful ways), but they don’t need to know EVERYTHING before they get a chance to think about a concept. In fact, experiencing the phenomena and processing it as a group with their teacher can help students cement the schema in their long term memory, which they can then recall and use as they dive into the details about the concept and learn new vocabulary and concepts. Go Schema theory!

References:

- Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 717–726.

- Chew, S. (2022) Having Knowledge Is Not the Same as Using It, The Teaching Professor, Dec. 12, 2022