This is my favorite cognitive psychology/teaching and learning demonstration because the resulting data is evidence of possibly the most important lesson we should take away from memory theory. As Daniel Willingham said: “Memory is the residue of thought.” One of the most important ideas we should build learning experiences on is this: the more deeply we think about something, the more likely we are to encode those thoughts into long term memory.

This is a foundational idea, but we often forget it. As students, it’s tempting to use study methods that feel good and are less effortful, but effortful studying is more likely to involve deep processing and increased learning. As teachers, it’s easy to fall prey to the curse of knowledge and fail to attend to the cognitive work students need to do to learn.

In about 15-30 minutes, this depth of processing demonstration can help “prove” the learning value of deep processing by gathering data “live” in a class or professional learning session. Here’s a more complete write up of the activity – Depth of Processing –

- Look through the slides for the activity to make sure the directions make sense, and make sure everyone has a way to write down responses (paper/pencil or digital response)

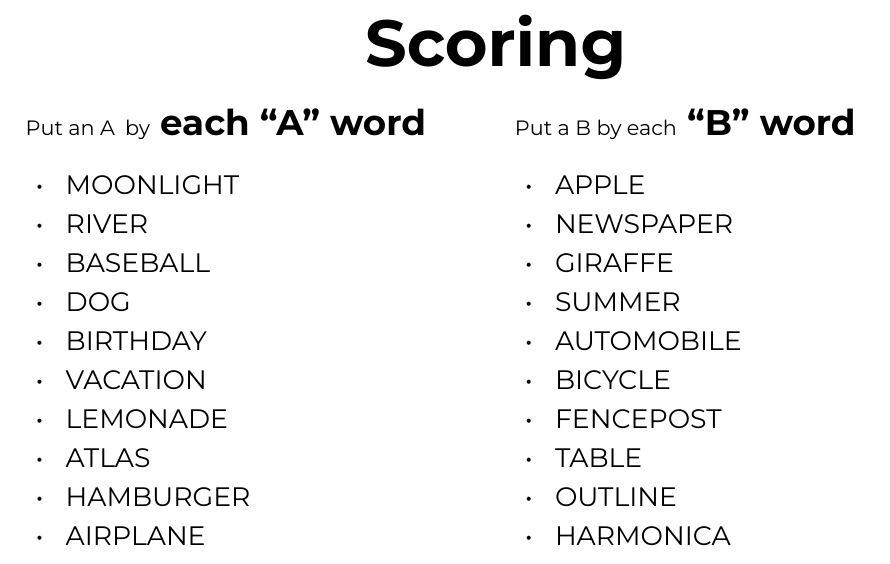

- By the end of the activity, everyone will have a list of words they remembers from the 20 “A/B” word list, and they will have “scored” how many A words and B words they remembered.

- Ask participants to report their number of A and B words somehow (recording the distributions on a white board or google form)

- At this point it should be pretty obvious that participants remembered more B words than A words (usually about 2 more words on average).

As you discuss with participants why we remember more B words than A words, the point of the activity should emerge out of the data: we remember more B words because the activity requires participants to deeply process B words, while A words are only shallowly processed.

When I get to discus this activity with teachers and students, we often gradually get to a simultaneously mundane and profound realization: the “harder” we think about something, the more likely we are to learn it. While this shouldn’t be a surprising conclusion, it starts great conversations about studying and teaching. If we accept this basic, foundational fact, then one of our most important jobs as students becomes figuring out how to deeply process what we need to learn. How to pick study methods that “force” us to deeply process information. And our job as teachers becomes crafting learning experiences that increase the chances that students will do the deep processing cognitive work that is likely to result in encoding to long term memory.

References:

- Willingham, D. (2021) “Ask the Cognitive Scientist: Why Do Students Remember Everything That’s on Television and Forget Everything I Say?“, American Educator, Summer 2021

- Wootter, E. (2018) “Making STEM’s Relevance Clear,” Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts North Adams, MA, PKAL Regional Conference, January 10, 2018

- Chew, S. (2010) “Improving classroom performance by challenging student misconceptions about learning,” APS Observer, 23(4), April