I stumbled across a couple studies related to bias and schools recently, and they got me thinking.

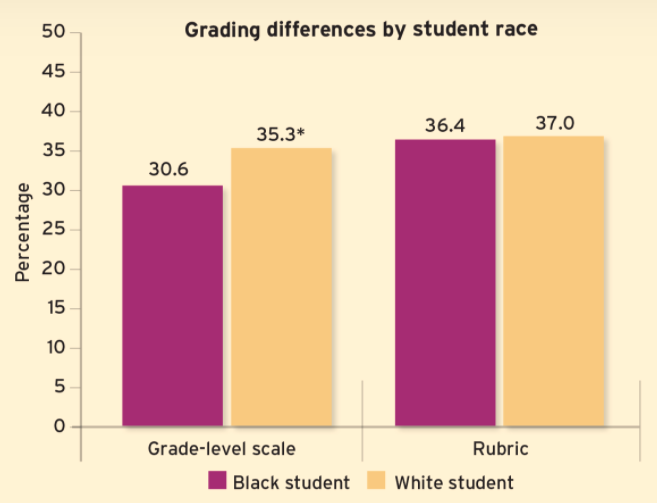

Study #1: Quinn, D. M. (2020). Experimental Evidence on Teachers’ Racial Bias in Student Evaluation: The Role of Grading Scales. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis , 42, 375-392.

In this study, Quinn looked at the scores teachers gave students on samples of their writing. His findings show evidence of racial bias overall, but this bias disappeared (mostly) when teachers used a rubric when scoring. Here’s a good summary of the study written by Quinn, and this graph represents the main results well:

One surprising (and potentially important) finding is what Quinn did NOT find. He had participating teachers take the IAT test for implicit racial bias. He found no relationship between scores on this implicit bias test and the grading differences he measured. This finding (and other criticism about predictive validity and the IAT test) makes me wonder if the time spent discussing implicit bias in schools is worth it? And maybe I should retire this “live” implicit associations test demonstration? Maybe we should spend our time talking about how to mitigate the influence of bias in our teaching (with techniques like using rubrics) instead of analyzing our possible implicit biases?

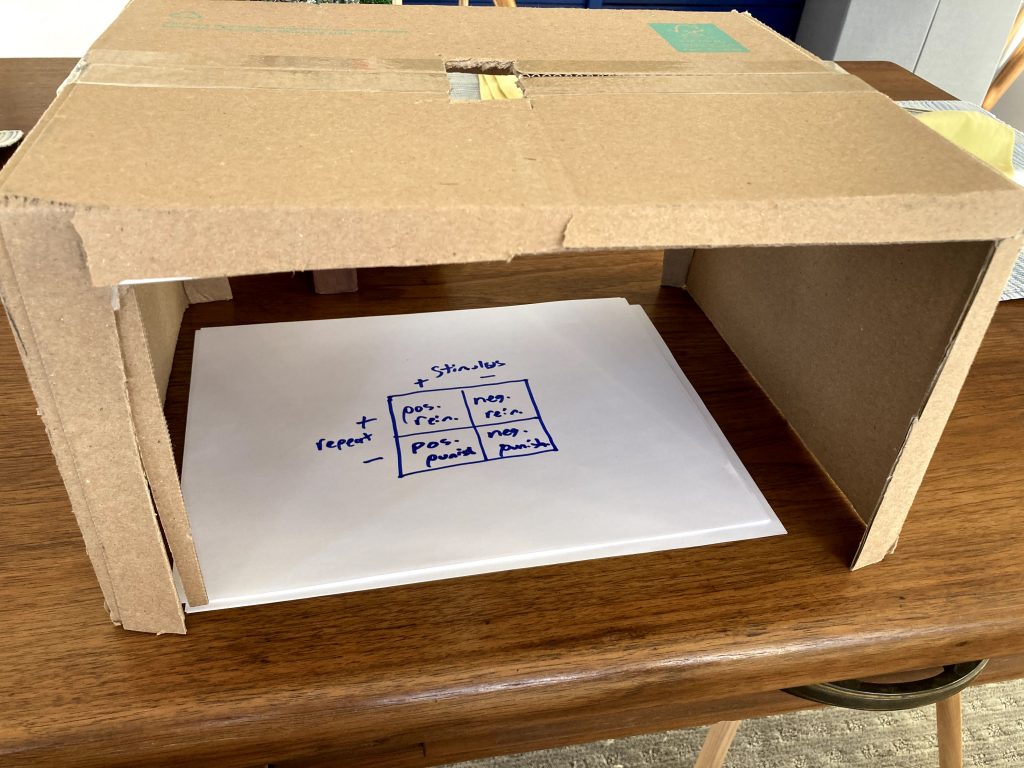

Study #2: Francis, D.V., Oliveira, A.C.M. De, Dimmitt, C. (2019). Do School Counselors Exhibit Bias in Recommending Students for Advanced Coursework? The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 19(4), 1-17.

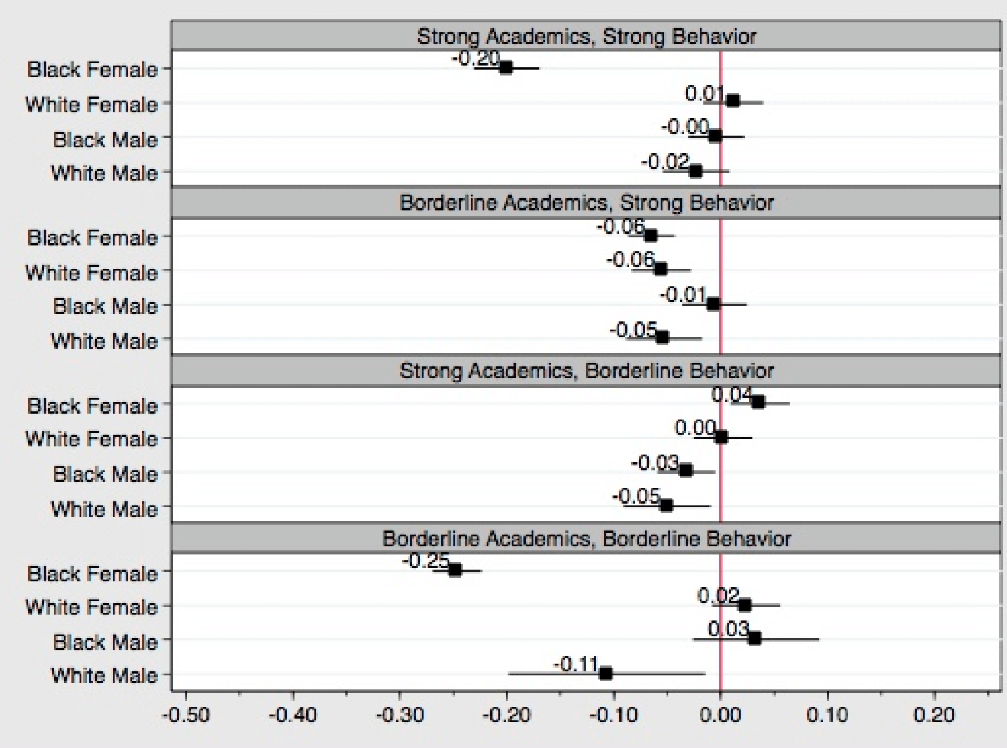

This study could start useful discussions in every high school with AP and IB courses. Here’s a quick summary. The authors use a clever methodology to investigate whether high school counselors may unintentionally be influenced by their biases when recommending students for advanced courses. Many people are familiar with the well-established finding that job resumes that include names that employers interpret as “black” names are less likely to result in calls for interviews than resumes with names that employers interpret as “white.” Francis, Oliveira, and Dimmitt used this same technique with “student resumes” and high school counselors. High school counselors judged student records and made recommendations about whether students should be allowed to enroll in an AP Calculus class. This figure represents one of their most important findings:

The authors describe their main conclusion: “… black female students are uniquely disadvantaged. School counselors are significantly less likely to recommend them for AP Calculus in both the weakest and strongest profile scenarios. In fact, the black female transcript in the strongest academic and behavioral profile was equally as likely to be recommended for AP Calculus as the blinded profile in the weakest academic and behavioral profile.” This clever study about bias could be used by high school counselors and school/district administrators as a starting place for potentially important discussions about how race and gender bias may be influencing academic opportunities for students.

UPDATE: My friend Josh shared these two citations with me (thanks Josh!) Based on the abstracts, I think they may be useful in this overall discussion:

Copur-Gencturk, Y., Thacker, I. & Quinn, D. K-8 Teachers’ Overall and Gender-Specific Beliefs About Mathematical Aptitude. Int J of Sci and Math Educ (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10104-7

Copur-Gencturk Y, Cimpian JR, Lubienski ST, Thacker I. Teachers’ Bias Against the Mathematical Ability of Female, Black, and Hispanic Students. Educational Researcher. 2020;49(1):30-43. doi:10.3102/0013189X19890577