Last day! And it was really a half day: one breakout session first thing in the morning and then the final keynote speaker.

Those of you who know me won’t be surprised that I filled my half day with Dylan Wiliam 🙂 The morning breakout session was a Q&A. Each table generated one question to ask him and he used the whole 1.5 hours answering these 5-10 questions.

I asked him two questions:

Question #1: Let’s say a teacher wants to change ONE teaching habit this year (knowing that habit change is difficult and takes a long time to do), what one habit related to formative assessment would you advise that teacher to change? D. Wiliam’s Answer: [pause…pause…] wait time. [laughter from the crowd]. He explained that changing wait time is hard to do and potentially very useful. He clarified something I’ve never heard before about wait time: we think of the wait time that occurs after we ask a question (he called this “thinking time”), but there’s also wait time that occurs after a student answers (he called this “elaboration time”). He recommended that we focus on this second aspect of wait time. When a student responds, wait before you indicate “correctness.” Have that student keep thinking. Get other students to comment on that answer. Get everyone thinking about that answer (deep processing!). He cited a study by M. Rowe “Slowing down is a way of Speeding up” that I need to find and read.

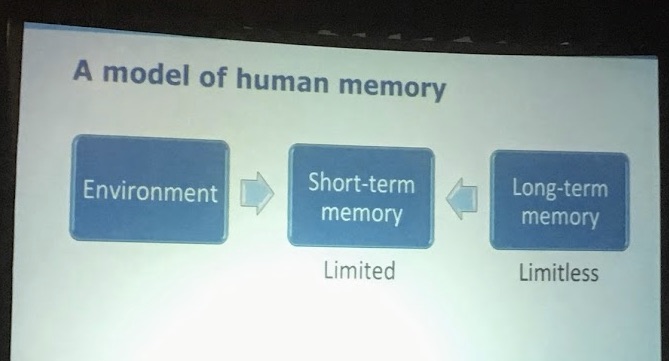

Question #2: For this question, I actually… lied a bit. Yep, I lied to Dylan Wiliam. Please don’t tell him. I told him that I was a former high school psychology teacher (true) and that I was working with a group of other psychology teachers (partial lie – I’m working with a bunch of former students of mine who now work as teacher coaches, district office admin, etc. ) to develop professional develop stuff based on the 3-box memory model – I asked if he knew of other work like this and if using this model seemed like a good idea (note: I “lied” b/c I didn’t want to spend the group’s time listening to me explaining how this group got together, what our roles are, etc.) D. Wiliam’s Answer: he said he thought it was a good idea to use the 3 box model and that the tricky decisions will be how far to go into the details. He cited a potential point of disagreement between Bjork (desirable difficulties) and Sweller (cognitive load theory). He advised us to make a “clean” version of the model and use that as a place to hang concepts and research on to (and that’s our plan!). I got the idea to ask Wiliam this question because of a slide he used very briefly during one of his presentations:

It’s great to get some “affirmation” from D. Wiliam that our plan to base a chunk of professional development on the 3 box memory model might be a great idea! (I bet I’ll write about these plans on this blog in the future)

D. Wiliam’s Keynote: the last event of the conference was a keynote address called “Negotiating the Essential Tensions.” It was good, but… too ambitious? Wiliam tried to cover a LOT of ground, shared a LOT of research, and I took a LOT of notes. I think I wish he would have focused on a few issues and gone deeper. But: he’s Dylan Freaking Wiliam, and it was a fascinating, enagaging presentation!

One aspect of the keynote that will stick with me: his cautions about jumping to “sweeping” (and standardized) answers about grading. He used some theory, analysis, and research to eloquently review some of the very complex issues involved in grading. Highlights:

- NO grading system is perfect, which means that every system involves trade offs. If we’re not clear about what those trade offs are and which ones we’re choosing, we’re not making informed choices about our grading system.

- Educators have been worried about the validity of grades for a LONG time (and Dressel 1957 ).

- There are important interaction effects between feedback and grading (Butler 1988)

- Everything is contextual: there are realistic scenarios when feedback might be more useful if it violates some of the “rules” we learn about feedback: sometimes feedback might be more useful if it is LESS specific, LESS timely, and LESS constructive. Context = important. The purpose of feedback is to help students improve performance on a task they haven’t done yet, not the task they just completed. He says Hattie doesn’t make this point, and he should (there’s a Kluger and Denisi meta-analysis that makes this point, but I haven’t found it yet).

- The old phrase “You don’t fatten the pig by weighing it.” is … wrong. Retrieval practice research indicates that students learn from tests. Frequent, low or no stakes testing is a really good idea (and might be one of the most powerful things we can do). Roediger and Karpicke 2006 and Bangert-Drowns, Kulik, and Kulik 1991

Whew! It was a great conference, I’m glad I went, and I’m walking away with a bunch of ideas. Thanks to my district for supporting my travel, and thanks for reading all this!